The Amazing Radio London Adventure |

Ben and Ronagh see in the New Year with a couple of Beatles, Ben does John Lennon a favour and tells Sir Joseph Lockwood some home truths about 'pirates' and their lucrative business

The dawn of 1966 was approaching, so Harold Davidson decided that Ronagh and I should accompany him and Marion to a New Year's Eve party at Norman Newell's flat in Baker Street. This was the part of the street where the fictional Sherlock Holmes was supposed to have lived.

Norman Newell was a songwriter and record producer for EMI. Some years before, Norman had added English lyrics to the music from the movie 'Mondo Cane' which had produced a hit record 'More', for both Perry Como and Jimmy Young.

A number of celebrities were in attandance at Norman's party, including John Lennon and George Harrison. There was also Sir Joseph Lockwood, managing director of EMI. Almost to the minute we arrived, John Lennon cornered me and we went with George into a small sitting-room by ourselves. John and I sat down in the middle of the floor, Indian style, and he lead off with, "Ben, what the hell are you doing playing my father's record?" I explained that I played the record mainly because of the human interest value as opposed to the record's quality.

To explain the scenario that lead to this discussion, some record producer had found Freddie Lennon washing dishes in a London hotel. He got Freddie to record 'That's My Life (My Love And My Home)' an old Walter Brennan-type record in which he talked over music. The words explained how Freddie had gone to sea and had left his young son John, and had never returned. A real 'sob' story, it was released on the PYE label. Don Agnes had given me the record and said that he realised that it was not all that great, but since it was John Lennon's father, it might be worth a play or two.

John told me that his father had left him with his aunt when he was three years old. He said he walked out of the door and never returned. I said, "John, it looks to me that your father might be really sorry that he walked out on you.' He replied, "If he were really sorry, he would have been back before now. He just wants to make same money riding on my shirt tail." I could see that John was really incensed over this matter, so I told him that the next time I went out to the ship, I would take the disc off the air.

After my promise to John, things lightened up for a while, until my next round with Sir Joseph Lockwood.

After my promise to John, things lightened up for a while, until my next round with Sir Joseph Lockwood.

(Left) Billboard Magazine, International Section, March 6th 1965

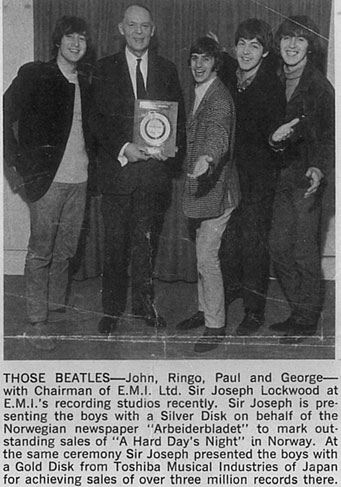

Harold Davidson and Sir Joseph were friends of long standing. Harold told Sir Joseph at the party that he thought it would be a good idea for Sir Joseph and I to meet and exchange ideas on records and broadcasting. Sir Joseph told Harold that he had never met with any 'pirate' and that he would never lower himself to do so. Harold, however, had some very strong powers of persuasion and soon I found myself in a little sitting-room face-to-face with the world's most powerful record mogul.

Sir Joseph started by saying, "Mr Toney, you are killing my record business!" I explained to him that Radio London was giving him far more exposure for his records than he was getting on Radio Luxembourg, yet he was having to pay for his air time over there. He finally conceded that I was right on that assumption, but he went on to say that I was playing only one style of music and that lowered his profits. He thought that, like the BBC, Radio London should be playing a greater variety of music. I explained to him how the American concept worked. In the States, certain stations are devoted to Top 40, others are confined to easy-listening music, and others play country and jazz. He really had no argument with this concept, but we never got around to discussing his main problem.

Sir Joseph's real problem was that because of the 'pirates', he was losing control of a vast empire that only EMI and Decca had under their thumbs from day one. The BBC was meaningless for record promotion because the Performing Rights Society demanded that they play any one record only once daily. Before the 'pirates' came along, only Radio Luxembourg was available as a promotion outlet and since EMI and Decca purchased between them the greater number of hours on that station, they ruled the industry. Shortly after Radio London went on the air, our ratings were running neck-and-neck with Radio Luxembourg. Big L pretty well had the daytime ratings, but at night, 208, with its 750,000 Watt transmitter sited in the Grand Duchy, had the greater coverage and larger audience.

In my job at Radio London, I didn't care whose record I played. It could have been from EMI, Decca, PYE, Philips, or one of the smaller companies. It only had to sound good. This was the real problem Sir Joseph was facing. I was giving recognition to some of his competitors that he had never had to deal with previously. EMI and Decca were somewhat like old divine-right kings, who held firm control over their subjects. Once their subjects rebelled and demanded a more democratic government, they had to step aside and make way for the public at large. It was really the 'pirates' recognising the output of smaller record companies, that chipped away at EMI and Decca's profits, not the style or the frequency of airplays of the records.

At the end of our conversation, Sir Joseph asked me about our profits. I told him that Radio London had cleared close to $7,000,000 profit in the past year. He seemed astounded that there was that kind of money involved and finally commented, "I thought you were just a group of boys out there messing up my business!"

To my knowledge, I was the only 'pirate' who ever spoke with Sir Joseph Lockwood. I found him to be a very sincere and thoughtful man, but a man who was caught up in a different time and a different concept of record promotion.

In the end, John Lennon, George Harrison, Harold Davidson, Marion Ryan, Ronagh and I, gathered in the living room along with Norman Newell and the rest of his guests, and sang-in the New Year to the strains of 'Auld Lang Syne'.

Editor's note: No doubt to John Lennon's chagrin, his father's single 'That's My Life (My Love And My Home)' had already gained a new entry at #33 in the Fab Forty that aired on January 2nd 1966, and it rose the following week to #28. Presumably all this happened before Ben was able to instruct anyone aboard the Galaxy to hurl it through the nearest porthole.

Ironically, a mint-condition copy can now command around £75.